The Istanbul Pogrom and the Struggle of Non-Muslim Minorities in Türkiye

- Elif Kılıç

- Sep 6, 2023

- 3 min read

As we remember and commemorate the 6-7 September 1955 Istanbul Pogrom on its 68th anniversary, let’s walk through the background of the events and the casualties and political consequences they caused while reflecting on the issue of minority rights in Türkiye.

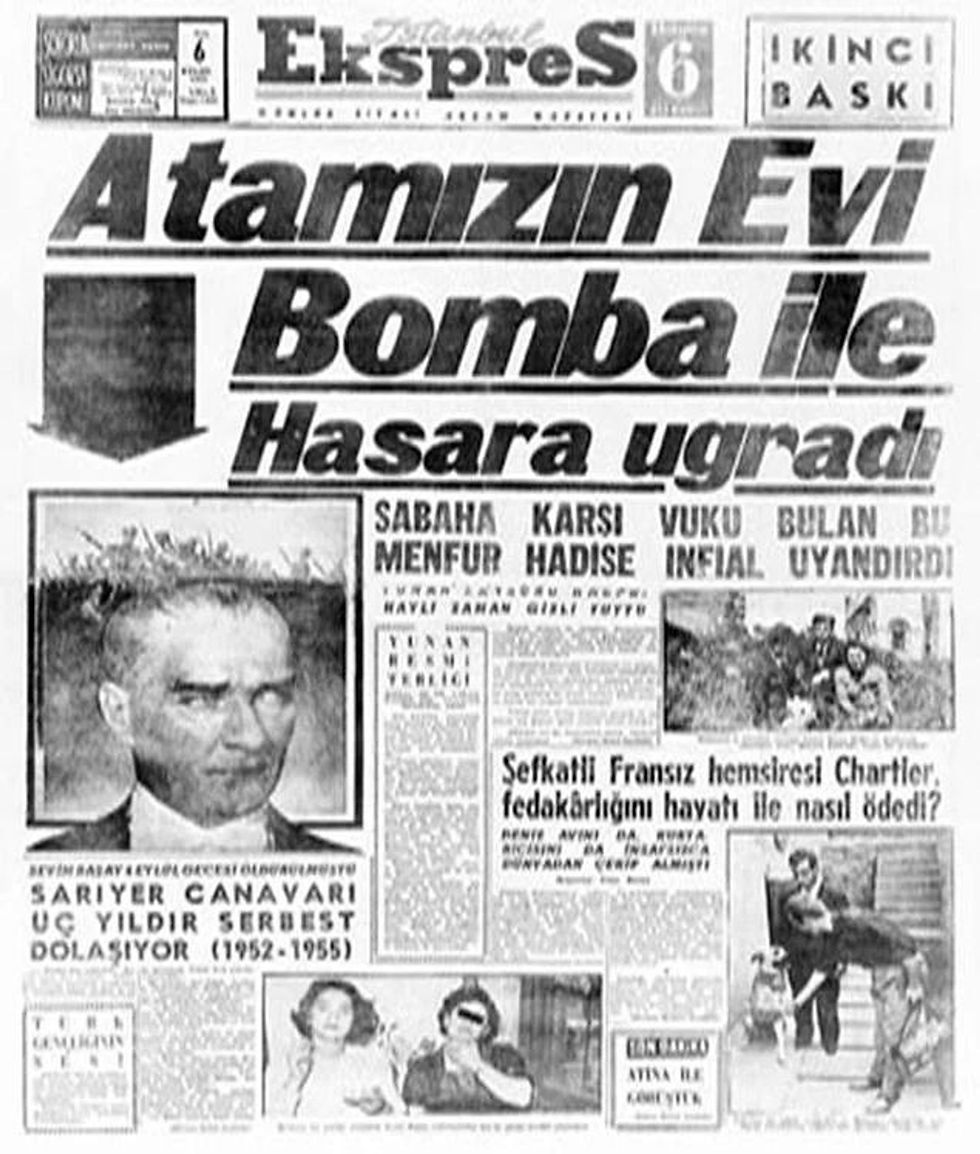

The House of Our “Ata” was Harmed by Bombs: This heinous incident, which took place in the early hours of the morning, caused outrage. Istanbul Express, 6 September 1955.

The Istanbul Pogrom was a series of events of mob violence directed against Istanbulite Greeks, yet it ended up harming other Christian -and even Muslim- minorities throughout Asia Minor. Besides the Greeks, Armenians and Jews also suffered harm from the pogrom. Even Muslim-convert Belarusians were targeted. It was backed by the government of Türkiye at the time, with the aiding of Adnan Menderes, who is known for his Islamist and liberal economic policies as the country’s prime minister. Istanbul Express, the renowned supporter of the Adnan Menderes government, published unfounded news about how Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s, the founding father of the Republic of Türkiye, birth house in Thessaloniki was bombed on its splash page of the September 6, 1955 issue. The issue was printed 14 times more than the other issues of the same newspaper and was especially promoted and put into circulation by the members of “Kıbrıs Türktür” (Turkish for “Cyprus is Turkish”), an association advocating for the Turkish annexation of Cyprus. It is also important to note that the association was freshly founded before the pogrom, in August 1954.

A bomb installed at the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki triggered the attacks. Later, it was discovered through his own confession that a Turkish usher was behind the installation. The Turkish intervention was further proven by the Yassıada trials in 1961.

The mob mainly focused on destroying the buildings and establishments owned by Istanbulite Greeks, with less emphasis on killing individuals. Still, many individuals died as a result of the attacks, and nearly 37 were injured in several other ways, according to unofficial and official sources. However, according to Dr. Dilek Güven from Sabancı University, the mob attempted to destroy instead of murder upon a command from organizing parties to keep the pogrom less controversial in the national and international press. Statistically, 4214 houses, 1004 businesses, 73 churches, a synagogue, two monasteries, and 26 schools were either completely or partially destroyed.

Attackers at Istiklal Avenue, Beyoğlu.

5104 arrests and a declaration of siege followed the tensions. Especially the members of “Cyprus is Turkish” and communists were meticulously investigated. The shade on communists can be explained by the fact that Turkey had just joined NATO four years ago and it was in the midst of the Cold War. Well-known Turkish intellectuals, such as Aziz Nesin and Kemal Tahir, were detained under the framework of the investigation of communists within the pogrom. On September 10, 1955, the Interior Affairs minister Namık Gedik resigned and left office. The “Cyprus is Turkish” association was also closed down. A few years later, after the 1960 coup d’etat, Adnan Menderes’ party was subject to penalization. The pogrom is occasionally compared to Kristallnacht, a pogrom against Jewish people of Europe in 1938, a year before World War 2.

Anatolian Greek-speaking population has been shrinking, especially after the population exchange in 1927. The pogrom played a huge role in accelerating this process. In Istanbul alone, the Greek-speaking population decreased from 65,000 to 49,000 in just five years after the pogrom. Today, the number of Turkish citizens of Greek descent is estimated around 3,000 while it was 120,000 in 1927.

To make a comprehensive examination of the hostile attacks, it is important to put it under the light of the Cyprus conflict. Some sources have suggested that the events served as a foundation for the polarization of the island as well as the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

Today, we remember those who lost their lives to and suffered material and spiritual damage from ethnic violence during the Pogrom and all around the world during various attacks and genocides.

Works Cited

De Zayas, Alfred. “[Septemvriana] The Istanbul Pogrom of September 6-7.” Futuristika, 14 Sept. 2022.

Erdemir, Aykan. “The Turkish Kristallnacht.” Politico, 7 Sept. 2015.

Korucu, Serdar. “‘6-7 Eylül Yine Yaşanır Diye Türkiye’den Ayrıldık.’” Agos, 6 Sept. 2019.

“‘Özel Harp Işiydi ve Muhteşemdi’: 6-7 Eylül Pogromu ve Bir Sabri Yirmibeşoğlu Portresi.” BirGün, 6 Sept. 2022.

Edited by: Melisa Altıntaş & Yağmur Ece Nisanoğlu